8 October 2025

The verb deplatform is a relatively new one. Merriam-Webster defines it thusly:

: to remove and ban (a registered user) from a mass communication medium (such as a social networking or blogging website)

[…]

broadly : to prevent from having or providing a platform (see platform entry 1 sense 3) to communicate

Merriam-Webster gives a date of 1998 for deplatform in this sense, but they don’t provide a citation, and the earliest use of the term that I’ve been able to find is from 2014. It appears in a tweet by Org. for Women’s Lib on 11 April 2014:

Resistance to the blacklisting of feminists IS possible. After months of deplatforming and blacklisting attempts,...[inactive link to a Facebook post]

Another early use on Twitter is on 25 February 2015:

no, that was me criticizing the hypocrisy and ideology of GG. not asking for her to be deplatformed for being anti-feminist

The tweet this is in response to has been deleted, so the identity “GG” is uncertain.

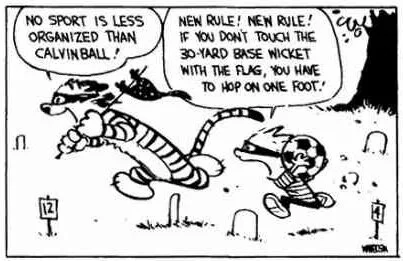

Another early online use appears in a discussion of a video game that allows users to hit fascist protesters with a purse. The game is Handväska! (Swedish for “handbag”) and was inspired by a famous 1985 photo of Danuta Danielsson hitting a Swedish Neo-Nazi marcher with her purse. Danielsson was a Polish Jew living in Sweden whose mother had survived Auschwitz. The game was created in 2017 and reported on by the Australian gaming website Kotaku.com.au on 10 February 2017. Comments on the article developed into a broader discussion of how to address hate speech and included this:

I’m not saying that any group is required to take this shitstain seriously or give him a platform to speak. I would much rather see hate speech law actually enforced against him than not.

Delegitimise and deplatform people like this through ridicule or argument. Disrupt their ability to speak through non-violent protest.

A few days later, 22 February, deplatform was used on the American website Salon.com, and the word began to be adopted by traditional media:

Everybody loves free speech until they don’t. The exact opposite is the case with “deplatforming,” which is what recently happened to former Breitbart editor and professional troll Milo Yiannopoulos. He was originally scheduled to speak this week at the Conservative Political Action Conference but saw his invitation rescinded after videos resurfaced in which he appeared to defend pedophilia.

Initially, deplatforming was primarily used to refer to rescinding an invitation to speak at an event, as in the Yiannopoulos case referenced in the Salon quote. But the term has widened to include banning those with controversial views from social media platforms, as it is in the December 2018 article on Mashable.com:

Over the past year, internet companies wielded the hammer known as “deplatforming” more than ever. Deplatforming, or no-platforming, is the term for kicking someone off social media or other sites when they break the rules by, say, using hate speech, or participating in harassment campaigns. Getting deplatformed means that the rule-breaker can no longer use that platform to share their thoughts or feelings with the world.

Deplatforming is itself a controversial tactic. Those who have been deplatformed often claim that their rights to “free speech” have been violated, which may be true in some cases where a public university (i.e., the government) has disinvited a speaker. Others claim that while it is legal, it violates the idea that challenging abhorrent views in the “marketplace of ideas” is the best way to counter them. Others disagree, saying that deplatforming is a prime example of the marketplace of ideas in action. The tactic does, however, seem to be effective, in that people with odious views like Yiannopolous and Alex Jones have seen their influence drop markedly after losing their platforms.

Sources:

Alexandra, Heather, “A Game Where You Go Bowling for Fascists,” Kotaku.com.au, 10 February 2017. (No longer available.)

Kraus, Rachel. “2018 Was the Year We (Sort of) Cleaned Up the Internet.” Mashable.com. 26 December 2018.

Merriam-Webster.com, accessed 4 September 2025, s.v. deplatform, v.

Nyberg, Sarah (@srhbutts). Twitter.com (now X.com), 15 February 2015.

Org. for Women’s Lib (@orgwomenslib). Twitter.com (now X.com), 11 April 2014.

Torres, Phil. “Milo, Donald Trump and the Outer Limits of Hate Speech: When Does Absolute Freedom of Speech Endanger Democracy?” Salon.com, 22 February 2017.

Photo credit: Hans Runesson, 1985. Wikimedia Commons. Fair use of a low-resolution copy of a copyrighted work to illustrate the topic under discussion.